June 2020

One Pub, Two Families, Three Annas, and Four Missionaries

Upper Moutere

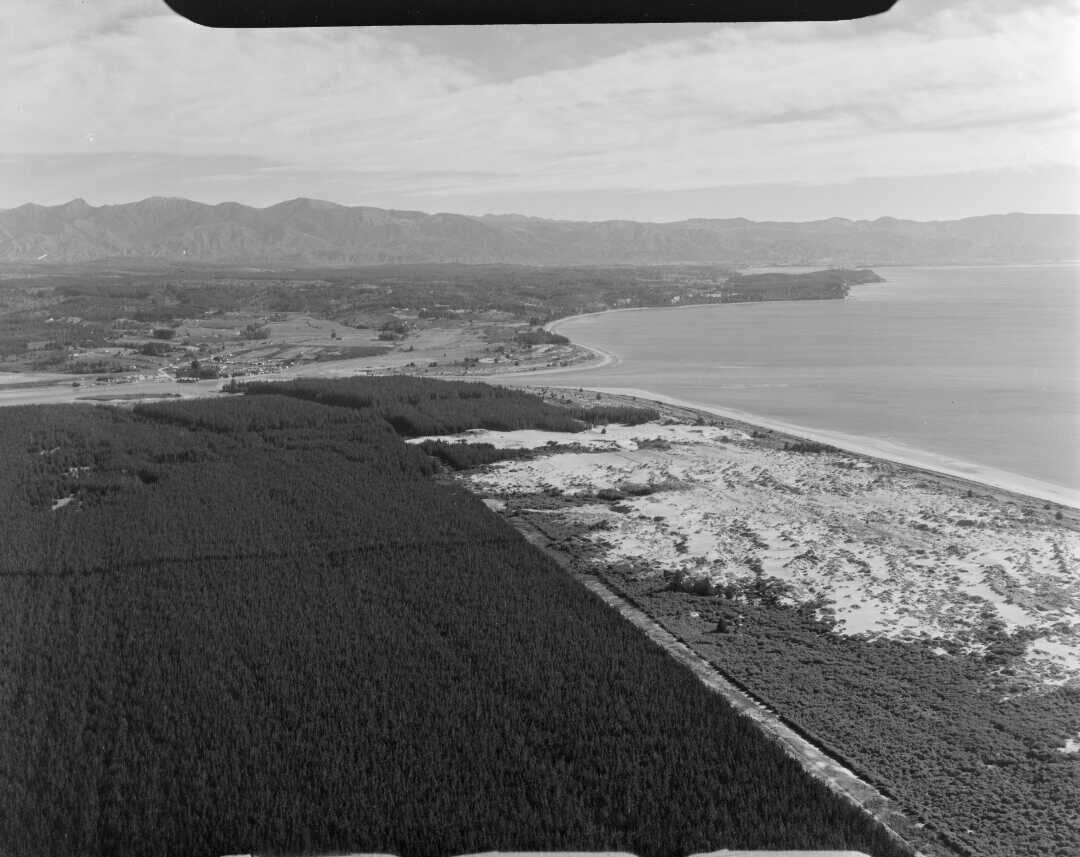

Tucked away between the rolling hills, 35km southeast of Nelson lies the quaint village of Upper Moutere. Home to acres of grapevines, apple orchards, and New Zealand’s oldest pub, the small village has a surprisingly big history.

Met with a sudden 50km limit, those passing through have no choice but to slow down and take in the olden time surroundings. Tree framed roads, clear views of the snow-kissed Arthur Range, and a modest arrangement of locally beloved stores, driving through Upper Moutere feels like a brief trip back in time. However, to the wider Tasman and Nelson dwellers, the village appears no more than a small splodge on the map, simply a pass-through en route to more popular locations.

The story of Upper Moutere is the subject of residents Jenny Briars and co-author Jenny Leiths’s 1993 book ‘The Road to Sarau: From Germany to Upper Moutere’. Whilst a part of a team organising the village’s 150th celebrations, Briars raised her hand to create a booklet. She soon realised that large segments of Upper Moutere’s fascinating history have been left untold.

The village’s history shines on through the old-time buildings and scenery. Its old-world charm can be attributed to its original inhabitants who pioneered the community from the ground up. Two families, names still present and familiar in the village to this day, permeate its history: Heine and Bensemann. Without them, Upper Moutere would certainly be a different place to how it is today - if it would exist at all.

Cordt Bensemann, a Hanoverian regimental serviceman, became intrigued by the thought of emigration while in London. He read about new colonization schemes during his time as a Guard of Honor at the Victorian coronation. Previously, Hanover had sent several regiments to Neuseeland to assist the new Crown colony. Unfortunately, the possibility soon became slightly more elusive, as Hanover had laws preventing a female monarch - the moment Victoria ascended, Hanover split from the British Empire. Cordt persisted. The New Zealand Company, headed by entrepreneur Edward Gibbon Wakefield, was offering parcels of land to any willing families. By signing up he took a great risk, as like many of the soldiers embarking on the journey he was deserting. He was court-marshalled in absentia and sentenced to death.

In December 1842, Bensemann, his wife Anna, and their four young children were instructed to wait at Hamburg port while their ship, the St Pauli, readied to sail to the mythical Neuseeland. It was a harsh winter, and whilst waiting in lodgings, ill-prepared for the length of their stay, the youngest child Margarita passed away in the night. Pressing through in hopes of new opportunities across the globe, they sailed for six months, alongside five other families, setting anchor in Nelson the following June. Hamburg's New Zealand Company agent, John Nicholas Beit, reportedly caused quite the havoc on the journey over. “He was a really horrible man. He was nasty to all the settlers”.

While in charge of food rations, “if people stood up to him he would put them on bread and water rations, he bossed around the ship's captain, bossed around the missionary’. A couple of German settlers got off the boat half-way and complaints were laid. On arrival, Beit neglected his responsibilities and subsequently abandoned his mission, perhaps for the greater good of the other immigrants.

Once the Saint Pauli had docked, Bensemann and his family settled by the mouth of the Waimea River. Here Cordt was building shelters for the settlers and got work dismantling the wrecked immigrant ship, Fyfeshire.

On the same boat, Lutheran Missionary Johann Wilhelm Christoph Heine had different ambitions setting sail for the new colony.

“The 1840s was a time in Europe where there were a lot of mission societies in England, they then spread through Europe. They had a ‘lets’ go help other societies and take the message of the church’ mentality” states Jenny.

Accompanied by three other missionaries, Heine and his colleagues were assigned to various regions of New Zealand to spread Lutheran gospel to the Maori communities. Unfortunately for him, his assigned region of Nelson had a small Maori community, and those present were already devout. Resigning to a life of viticulture, he and other German immigrants founded a village called ‘St Paulidorf’ (named for their vessel of passage) in Harakeke, where the New Zealand Company had leased 100 acres of land for his parish. It wasn’t long until the foreign soils and flooding proved to be a challenge to the battered settlements, so much so that the settlers decided to draw their mission to a halt. Abandoning the area, they headed back to Nelson. Heine settled in the nearby Waimea Plains for the next few years.

During this time, Cordt Bensemann’s oldest child Anna took a fancy to Pastor Heine. Their 20 year age gap, Anna 15 and Heine 35 at the time, was not enough to interfere with their romance, the couple got married in 1849. The married couple moved to a new church in Ranzau. They lived here for the following three years before trading the Ranzau parish for two sections in Upper Moutere. Heine sold 80 acres of his Moutere land to his old friend from the St Pauli, now father-in-law, Bensemann.

It wasn’t until 1850, six years after the initial arrival, that Upper Moutere’s establishment properly commenced. In October of 1853, Pastor Heine, his wife Anna Heine, and daughter moved back to Moutere. The Moutere became the new centre for German settlement, though initially just two families, it started a movement. Over time the families wrote back to their German friends in Hanover and Hamburg, and the family later journeyed out and joined the community. The Heines purchased a 15 room house which became a place of church teachings and schooling.

“We have a beautiful little church. The cornerstone was laid on my birthday in 1864 . . .”

- Anna Heine, diary entry

Cordt Bensemann, already a trained builder, began the construction of his family home, using the materials available such as rough sawn timbers from the clearing of native bush in the valley. A subsequent two-storey wing was later added, now known as the Moutere Inn. Though the original rough sawn timber was demolished alongside the original veranda in 1960s renovations, the Inn still holds some of its original charm. Perhaps most impressively it claims the title of the ‘oldest pub in New Zealand’, but this is a controversial debate yet to be settled, according to Jenny.

“It was [Bensemann’s] house and he built the inn that the building [the current pub], was added on to. That's why they say it's the oldest pub. It's the oldest continuous pub, but other pubs say they're older.”

A stroll up the road from the pub is St Paul’s Lutheran Church. Framed by a small white fence and pleasant greenery, it is a sight for sore eyes. However, the Church we appreciate today has had quite the transformation from its original architecture.

"The church that's there now was built in 1905, but there was an earlier church built in 1864 and that was made of Kahikatea (white pine), it was prone to borer and rot and so was pulled down,” says Jenny.

There’s quite a story surrounding the bell that rings to this day. It was “cast in Hamburg and is inscribed in German. The bell is called Anna, named after the pastor's wife.”

The bell, which remains the same, cost twenty-five pounds, approximately £3,197BPS today, or $6365 NZD.

The foundation stone of the original church was laid on 2 November 1864, the day of Heine's daughter’s (also called Anna) birthday. She kept a detailed diary which is now regarded as an important record of the village’s history. In it she recounted her life being one of the elder daughters living in a household of fourteen children. Originally written in German Gothic text, the diary has been translated into English by her son.

The inside of the church remains with much of its original interior. German settlers brought many of the church's possessions with them, including silverware, candlesticks, and a crucifix.

The village's name holds history within itself. Upper Moutere used to be known as Sarau, named after an equally beautiful village in Northern Germany. Unfortunately, the change of name was a consequence of discrimination and unwarranted mistreatment against the German settlers during the war.

“Sarau was dropped during World War I. People who had a name that sounded German or foreign were looked at twice, especially here in a German village. People had bad thinking like, ‘we can't trust them”, explains Jenny. “Some people even changed their surnames. This was wanting to blend in ….they anglicized them to make them seem more English”.

Upper Moutere still stands out amongst the more modernised areas of the Nelson/Tasman region, wearing its heritage on its sleeve. Its enchanting feel can be credited to the founders, whose hard work can still be looked upon with appreciation and admiration∎